What I read in 2020

Pandemic reading, debut novels, classics, and more.

When the world stopped in mid-March, I was briefly elated: wasn’t time stopping exactly what I always wanted? I had fantasies of doubling my reading, endless quiet, uninterrupted time to write. Plunging into classics I haven’t read, making it through a canon list, etc, etc. Of course it didn’t turn out that way: 2020 was anything but a quiet year, and the absolute uncertainty about the future—an unsubtle synecdoche of our larger historical situation—coupled with the constant intrusion of crisis and hysteria eventually made it hard to do much of anything, including things I would ostensibly enjoy. By September or so I had nearly stopped reading entirely and turned to music, though music books helped me get back on track.

Still, I managed to at least keep pace with last year. I matched last year’s total number of books (36) and fell only slightly short in total pages read (13,159 vs. 13,641). I narrowly beat last year’s percentage of my reading that was in French: 17.4 percent vs. 15.8 percent. Not that the numbers matter, but I find they motivate me at least occasionally.

Now on to the content.

Fiction: in search of how to fill lost time

I began my “pandemic reading” by accident in January with Ling Ma’s Severance (2018), set in a post-apocalyptic America where a pandemic has turned the population into placid zombies and the narrator joins an increasingly cultish band of survivors. It was fun if not particularly memorable; my favorite parts were the hilarious passages about outsourced Bible production in China.

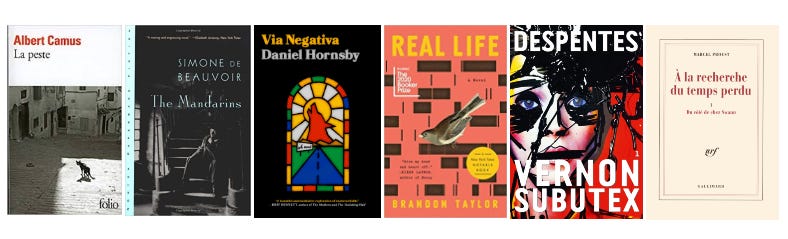

I continued on the COVID theme with, more predictably, Albert Camus’ La peste (The Plague, 1944). This is one of the literary classics I’ve reread the most since the first time in high school. I first read it in French in the early 2010s when I still needed a dictionary for every page. It topped the bestseller lists in France and America this year for obvious reasons, and dozens of articles were written about it; it struck me that where it is usually read philosophically and politically, this year it was being read as what it appears to be on the surface: a book about a plague. The pandemic parts were uncanny, especially the power of collective denial and the delusional belief, which I certainly exhibited this year, that the end of the plague is always just around the corner.

But I thought more about the political themes than the general public seemed to, partly because I followed it directly with Simone de Beauvoir’s The Mandarins (1954). Both books emerged from the same postwar Paris milieu, and The Mandarins depicts a fictionalized Camus wrestling with the literary sensation of The Plague in the quasi-revolutionary, politically-charged Paris at the end of World War II. Given the personal closeness of de Beauvoir, Sartre, and Camus, both books echo with similar philosophical and political concerns. The Plague is about the classic existentialist dilemma: the basis of ethics in an absurd, godless world, the responsibility of the individual before the, for lack of a better term, reality of evil. The Mandarins fictionalizes the real-life transposition of that concern onto the politics of Communism just before the onset of the Cold War: how far should intellectuals go in supporting the USSR as a world-historical force for a better future given what they were learning about its brutality in practice? As is well known, Sartre and de Beauvoir was on the side of “engagement”—intellectuals were morally obligated to intervene in politics—while Camus held on to the fantasy of autonomous, apolitical art. Though I side with Sartre and de Beauvoir there, the basic terms in which both sides posed the question—the morality of individual actions—seems to me a kind of almost Protestant obsession with perfect motives and a clear conscience that is something of a category error in political thinking.

(Speaking of these authors, I really enjoyed this essay on Simone de Beauvoir by Joanna Biggs, and this one in the New Yorker on the difficulty of translating the famous first line of Camus’ novel L’Étranger despite its simplicity. French Twitter had a few laughs about the fact that, as Olivier Tesquet put it, “The most limpid first line in French literature has been an untranslatable puzzle for the Anglo-Saxons for over 70 years.”)

A few other novels that stuck with me this year: my favorite, Daniel Hornsby’s way-too-under-the-radar Via Negativa (2020), about an aging, offbeat Catholic priest who, all but forced into retirement by conservatives in the church, takes off on a road trip across America with—wait for it—a coyote in the back of his car. Simultaneously hilarious—vicious commentary on the trashiness and idolatry of American evangelicalism—and wrenchingly sad, it was the most gripping book I read this year, full of strange characters and wildly imaginative scenarios. The way the protagonist is slowly revealed through his omissions and absences mirrors Hornsby’s carefully-dosed negative theology (hence the title). I also really liked a much-less-under-the-radar debut novel, Brandon Taylor’s justly celebrated Real Life (2020), in which a biology grad student wrestles not only with the trauma of all academic research—the violent, prolonged encounter with one’s deepest insecurities—but with other traumas past (growing up gay in the rural south) and present (the everyday racism of the biology lab, a romance with straight friend). I wasn’t quite sold on the final act, but several scenes were so tantalizingly paced and taut with emotional tension that I found myself holding my breath.

After so many helpings of Michel Houellebecq over the last few years, I feel like I needed the first volume of Virginie Despentes’ Vernon Subutex trilogy (2015, translation 2019), in which an aging record-store owner named Vernon is evicted from his apartment and couch-surfs his way through the entrails of contemporary Paris. Despentes and Houellebecq share certain attributes: rage against the heartlessness of society, sensitivity to the indignity of old age, and affection for the “losers” of modern life. Like Houellebecq, and in keeping with her reputation as the “bad girl” of French literature, she’s bracing and offensive, daring you to sympathize with people and feelings universally considered bad, from fascists to domestic abusers. But Despentes has a much wider palette of “losers”; unlike Houellebecq, her characters aren’t all middle-aged male nombrilistes, and her diagnosis of society’s ills aren’t rooted in an atavistic, pseudo-historical moralism. On page after page, she brings to life how the fight for economic survival under capitalism—both the brutal competition and the small, emotional indignities and lack of recognition—harden people into pathological versions of themselves. Vernon Subutex is much more truly “Balzacian” social novel than Houellebecq has ever written.

That brings us to the big one, the last book I finished in 2020, down to the wire on December 30th, keeping my recent tradition of finishing a French classic at the end of the year: Marcel Proust’s Du côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way, 1913), the first volume of À la recherche du temps perdu. I re-started it in April when I was having trouble sleeping and found that trying untangle the labyrinthine sentences tired out my brain. I read it in 50-100 page bursts the rest of the year, which works fairly well given the glacial pace of the narrative. I tremble before the task of describing it, but it’s something like a work of philosophy projected over a portrait of French bourgeois society in the late nineteenth century interspersed with art and architecture criticism. That sounds serious indeed, and I doubt the modern reader gets the full measure of Proust’s humor: the descriptions of the hypocrites, vulgarians, social climbers, and idiots in Parisian salons can be as witty as Jane Austen, but with the air that very specific real-life people are being satirized who would have been instantly recognizable to readers a century ago. Of course, the best part is the reason it’s a classic: the elaborate, stunning way it brings sensation, memory, and the construction of selfhood to life. And I was relieved to find it wasn’t as painful a workout for my French as I expected: that honor went to Sylvain Tesson’s La panthère des neiges (2019), a philosophical travelogue by France’s premier outdoorsman and National Geographic animal documentarian, which uses obscure vocabulary to express its reactionary view of nature. At times a beautiful book, though.

Other novels I finished this year and highly recommend: Elena Ferrante, the Neapolitan Novels (2012-2016); J.M. Coetzee, Disgrace (2000); Willa Cather, The Song of the Lark (1915); Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad (2018).

Nonfiction: somewhere between the 70s and the 2000s

I spent a lot of time this year learning and listening to music from the 1970s, from Television’s Marquee Moon(1977) to the disco, punk, and post-punk of the decade’s end. (I even listened to a podcast about the Grateful Dead). And it was actually in Bruce Schulman’s The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Politics, and Society (2002), another book I owe to a podcast, that I heard about the 1979 Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park in Chicago. (There’s also a bit about it, with footage, in the new HBO Bee Gees documentary, How Can You Mend a Broken Heart). Ostensibly a protest by rock fans against the rise of disco, it turned into something like a white riot against black music in general that today looks like a revealing case of “economic anxiety” taking nasty cultural form—as someone on Twitter put it, it looks like a Trump rally. Schulman (as I now only vaguely recall) interprets the 1970s as the decade America lost its grip, driven by Watergate, Vietnam, and economic crisis into pessimism and cynicism that expressed itself in the rise of the conservative movement and the end of the dream of racial integration, the “Southernization” of politics and culture, etc. (Another fact I didn’t know: Lynyrd Skynyrd’s now-beloved “Sweet Home Alabama” was a 70’s neo-confederate anthem by a band from—how prescient—Florida.) What was most fascinating to me is that the 70s were also the decade of generalized conspiracy theory and weird religion, from the New Age movement to fundamentalist evangelicalism, which I had never thought of as part of the same historical process.

My other major nonfiction challenge this year was Julian Jackson’s De Gaulle (2019), a biography of that giant of twentieth-century politics and inventor of the modern French presidency. At over 900 pages, I think it might be the longest history book I’ve ever read from start to finish, since we don’t exactly “read” as professional historians. In the end I think what is so fascinating about Charles de Gaulle is that he was an essentially nineteenth-century man—a parochial French nationalist with intellectual references and values that were already obsolete when he began his career—who managed to transcend his own anachronism. The biography is somewhat (and rightly) “deflationary” in showing that CDG was more dramatic and dogged than he was brilliant; in fact, he could be incredibly narrow-minded and self-defeating. But what struck me during this election year especially, is that if CDG had one area of brilliance, it was his mastery of the theatrics of state power, of what people more recently call “politics as spectacle”: the reality that in twentieth-century politics, how things are made to look is in a very real sense how they are. His “certain idea of France” was that it was more important and powerful than it actually was; he didn’t make it so, but he made French people believe it was so—to some extent to this day. Because De Gaulle was, ideologically, such an empty vehicle of his own self-belief and was obsessed with the drama of his own person, the parallels with a certain 21st-century politician are sometimes remarkable. (For more on how the book fits into the De Gaulle historiography, see this excellent review by Grey Anderson.)

The music books: the turn of the century in rock

My favorite type of reading is the sort I do when I’ve discovered what feels like a new world: a new zone of the book universe I hadn’t known existed. This year it was music books: a vast expanse of biographies, oral histories, memoirs by hangers-on, and occasionally more serious critical and academic takes on music as political and popular culture. It started, once again, with a podcast: one that led me to Lizzy Goodman’s Meet Me in the Bathroom: Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City, 2001-2011 (2017). The dense, 600-plus pages of interviews with and about the Strokes, Interpol, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and LCD Soundsystem, made visible a whole network I had failed to see about early-2000s NYC rock, despite living there and, incredibly, despite writing about music for a living myself. Not just bands I loved but the city I loved at an important time in my life came alive, and in the sprawling interviews you saw the larger historical forces that shaped the moment, from the fallout from 9/11 to dot-com money. It was my first experience of the uncanny feeling of watching a time you lived through solidify into history.

From there, my whole past as a music lover and writer seemed to come back to life, and I spent many pleasant hours listening to records and reading books about music. One of the most specific was Steven Hyden’s This Isn’t Happening (2020), a book about Radiohead’s 2001 album Kid A and the anxious end of the twentieth century it embodied. This was another recognition of another almost-lived historical moment: I am just a few years younger than Hyden, just old enough to have discovered, loved, and metabolized OK Computer and Kid A in time for the release of In Rainbows in 2007. Hyden’s most interesting point is that, even though it also expressed Radiohead’s nervous skepticism toward technology and consumer society, Kid A’s attempted murder of rock music by electronics and the drama surrounding its release reveled in an optimistic, emancipatory era of the internet that contrasts sharply with the curdled, corporate-dominated version we ended up with.

On the other end of the spectrum, that of broad historical sweep, was Robert Christgau’s memoir Going to the City: Portrait of a Critic as a Young Man (2005), which recounts the period from his birth in Queens, NY in the late 1940s to helping invent the genre of rock criticism at the Village Voice in the 1960s and 1970s. There’s something a bit off-putting about how proud he is that he was never a true sixties child or a hippie, his sort of backhanded celebration of his own normality (which comes out in in his occasional harshness toward music about sadness, pain, and dysfunction). But I still appreciated his attempt to articulate his theory of popular music, however underdeveloped, and very much appreciate his pioneering intellectual opposition to the romantic ideologies of authenticity in folk and rock. And I was grateful to the book for introducing me to the stunning and still-underappreciated feminist rock criticism of his ex-girlfriend Ellen Willis. Other music books I read this year include Chris Ott’s 33 1/3 volume on Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures; Andrew Beaujon’s reported book on Christian rock, Body Piercing Saved My Life (2006).

Coming up in 2021

Since it seems I’ve picked up the reading momentum I lost in the final quarter of 2020, I’m eager to get to the new novels I wanted to read last year: Phil Klay’s Missionaries; Hari Kunzu’s Red Pill; and Alice Zeniter’s Comme un empire dans un empire. And I’ll just mention one forthcoming book I’m looking forward to this year: Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts (February 2021).

What did you read this year? What do you think about what I read, or what I said about what I read? I’d love to hear from you. You can reply directly to this message if you’re a subscriber or email me here.

Note: You can follow me on Goodreads here.